Volume 6 - Year 2025 - Pages 97-104

DOI: 10.11159/jmids.2025.009

Designing Prompts for Shared-Experience-Focused Utterance Generation in LLM-Based Dialogue Systems

Rikuto Fukushima, Masayuki Hashimoto

Toyo University, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Department of Electrical,

Electronic and Communications Engineering

2100 Kujirai, Kawagoe-shi, Saitama, Japan 350-8585

s36C02500140@toyo.jp; hashimoto065@toyo.jp

Abstract - In modern society, the problem of social isolation and loneliness among the elderly living alone has become increasingly serious due to the progression of aging. Casual dialogue systems have gained attention as a potential solution to this issue. This study aims to build a casual dialogue system that facilitates shared-experience-focused utterances, where the system and the user engage in dialogue based on commonly recognized knowledge and experiences. Grounded in the theory of utterance classification incorporating insights from language education, the proposed system seeks to promote natural interaction through shared understanding. To achieve this goal, we refined our prompt design and conducted experiments focusing on text-based dialogue. This approach enabled us to test a wide variety of prompts, as the system’s performance was evaluated through LLM-to-LLM dialogue results assessed subjectively by the author. As a result, the proposed prompt design generated natural shared-experience-focused utterances while reducing contradictions with self-attributes and misinterpretations of given information. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of incorporating shared experiences and language-education-based utterance classification into prompt design for improving rapport in LLM-based casual dialogue systems.

Keywords: Prompt, Dialogue systems, Large Language Models.

© Copyright 2025 Authors - This is an Open Access article published under the Creative Commons Attribution License terms (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0).

Date Received: 2025-01-23

Date Revised: 2025-09-30

Date Accepted: 2025-10-26

Date Published: 2025-12-30

1. Introduction

The growing number of elderly people living alone in an aging society has increased the risk of social isolation and loneliness [1]. Such isolation reduces communication opportunities, leading to decreased mental vitality and cognitive decline. Casual dialogue systems have been proposed as an effective approach to address these issues [2].

Recently, dialogue systems based on Large Language Models (LLMs) [3] have attracted attention in elderly care and mental health support. Although these systems can generate natural responses, their content often lacks depth and empathy, making it difficult to sustain emotional engagement. In addition, LLMs face challenges such as hallucination—producing factually incorrect or fabricated responses [4]– [6]—and context loss during long conversations, which causes abrupt topic shifts or contradictions [7].

This study proposes an LLM-based casual dialogue system. The system focuses on shared-experience-focused utterances. These are utterances grounded in knowledge and experiences recognized by both the user and the system. By integrating insights from language education theories on utterance classification and shared knowledge, the system aims to promote empathy. It also seeks to maintain natural and engaging dialogues. To achieve this objective, we focus on text-based dialogue in the initial phase and will design and refine prompts accordingly.

2. Utterance Classification in Casual Dialogue

2. 1. Definition of Casual Conversation

According to Tsutsui [8], "a common definition of what constitutes casual conversation has not been reached among researchers." she further defines it as "a conversation conducted as an activity to spend time with a companion in a situation where there is no specific task to be accomplished, or during a period when a task is not being performed."

2. 2. Utterance Types

In analyzing casual conversation, Tsutsui [8] classifies utterances into four types: "questions," "reports," "shared-experience-focused utterances," and "monologues." Below, we explain each type. In this study, we omit the explanation of "monologues," which do not assume a specific listener, as we focus on the interaction between dialogue participants.

- Questions: Questions are utterances used by the speaker to elicit information or opinions from the listener and are a key element in shaping the flow of conversation. Figure 1 shows an example of question utterances.

|

A: Where was this photo taken? [Question] B: This is a photo I took at Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto during my recent trip. |

Figure 1. Example of Question Utterances.

- Reports: Reports are utterances where the speaker conveys their own information or opinions to the listener, serving to expand the conversation by providing new information. Figure 2 shows an example of report utterances.

|

A: I'm going to Kyoto again next month. [Report] B: Wow, that's perfect timing, the autumn leaves are beautiful now. |

Figure 2. Example of Report Utterances.

- shared-experience-focused utterances: Shared-experience-focused utterances refer to instances in which a speaker produces an utterance based on information or opinions commonly recognized by both parties. While questions elicit information and reports provide new information, shared-experience-focused utterances are unique in that they foster a sense of conversational unity by adopting the same perspective as the listener and drawing on common topics. Therefore, such utterances go beyond simple information exchange, serving instead to deepen the relationship between speaker and listener and to build rapport. Figure 3 shows an example of shared-experience-focused utterances.

|

A: Where did we meet up that day again? B: It was in front of the station ticket gates |

Figure 3. Example of shared-experience-focused utterances.

3. Related Work

Recent research on dialogue systems has focused not only on task-oriented dialogues, such as information provision and question-answering, but also on casual dialogue that emphasizes empathy and relationship building.

Rashkin [9] tackled the challenge of enabling dialogue agents to respond with empathy, pointing out that a major obstacle was the scarcity of suitable publicly available datasets for training and evaluation. To remedy this, they introduced EMPATHETIC DIALOGUES, a novel dataset of approximately 25,000 conversations, each grounded in a specific emotional situation. The dataset consists of one-on-one dialogues collected via crowdsourcing, where a "speaker" describes a personal experience tied to a particular emotion, and a "listener" replies in an understanding manner. Their experiments showed that dialogue models trained on this dataset are perceived as more empathetic in human evaluations compared to models trained merely on large-scale internet conversation data.

Similarly, Kasai [10] sought to enhance AI's empathetic capabilities by fine-tuning a large language model on "A Japanese Empathetic Dialogue Speech Corpus," which contains emotionally expressive dialogues. Their subjective evaluation experiments confirmed that the fine-tuned model was perceived by users as significantly more friendly and trustworthy than the original model.

However, these studies do not explicitly address utterances based on "shared experience."

4. Issues in LLM-Based Dialogue Systems

This study generates casual dialogue by assigning a role to an LLM using a prompt. The following issues have been observed, which undermine the naturalness and consistency of the dialogue. Issues 1) and 2) were frequently observed during the implementation of shared-experience-focused utterances.

- Contradictions with Self-Attributes: Despite being assigned a role in the prompt (e.g., "You are an office worker"), the generated utterances may contradict that role [11]. Such contradictions with self-attributes significantly impair dialogue consistency and give the user an unnatural impression. For example, even with the role setting of being an office worker, cases have been observed where the system says, "I worked on a project with colleagues during my student days," which is inconsistent with the assigned role. Furthermore, when an LLM is given a role name in the prompt (e.g., "You are Saito") and additional information such as "Saito went to XX in the past," the system may generate utterances under the mistaken interpretation that the Saito who went to XX is a different individual.

- Misinterpretation of Given Information: Even though the system is designed to proceed with the dialogue based on information explicitly presented in the prompt, the LLM may misinterpret that information [12]-[14]. For instance, a prompt might specify, "You know from the last conversation that the person you're talking to was planning a trip," but the actual dialogue may proceed under the assumption that the trip has already ended. This shows a problem with misinterpreting or misrecognizing the given information.

- Bias in Utterance Types from a Language Education Perspective: Most dialogue generation by LLMs is based on a structure where either the user or the system possesses information, and one provides it to the other. The utterance types in this structure are limited to either questions or reports. Consequently, generating shared-experience-focused utterances is difficult in such dialogue systems, because they lack the common experiences and knowledge necessary for these utterances. If a system could perform shared-experience-focused utterances, it is expected to contribute to building rapport with the user and improving user satisfaction.

5. System Configuration

Figure 4 shows the configuration of the LLM-based casual dialogue system.

To have an LLM generate shared-experience-focused utterances, it is necessary to include common experiences and knowledge in the prompt that instructs the LLM [15]. A database to store this information is also required. In this database, contents previously spoken by the user in past dialogues are registered as common experiences and knowledge shared between the user and the system [16]. As the dialogue progresses, the prompt is updated by extracting information to be included from the database based on the user's utterances and past interactions [17].

This study focuses on the design of the prompt among these components. Common experiences and knowledge are assumed to be available and are incorporated into the prompt for utterance generation. OpenAI’s ChatGPT is employed as the LLM.

6. Proposed Method

6. 1. Proposed Prompt Configuration

We propose the design of the prompt for the three issues mentioned in Section 4. Figure 5 shows the configuration of the proposed prompt. The proposed prompt consists of three components: instruction statements (specifying roles and constraining the system to output only one utterance), event details (information about past events and hobbies extracted from the dialogue history), and definition and examples of shared-experience-focused utterances [18].

- Instruction statements: Figure 6 shows the content of the instruction statements, one of the components of the proposed prompt. The instruction statements define the LLM's role in the dialogue (its own name and the name of the dialogue partner) [19] and specify the sources of information to be referenced. Furthermore, to prevent the LLM from generating multiple turns of utterances unintentionally, we impose a constraint on the output format: "Output only one utterance as is." In the illustrative example shown here, the name "Saito" is assigned to LLM A and "Fujita" to LLM B. Note that while Japanese prompts were used in this study, Figure 6 presents their English translations.

|

#Dialogue Instructions You are Saito (your dialogue partner is Fujita). Based on the premise that you had a previous dialogue, generate a shared-experience-focused utterance (refer to prerequisite knowledge) from the event details. Output only one utterance as is. Also, create a shared-experience-focused utterance based on the prerequisite knowledge. |

Figure 6. Instruction statements.

- Event details: Table 5 shows the content of the event details, one of the components of the proposed prompt. The event details [15] are the source of information for generating shared-experience-focused utterances. A long dialogue history described in natural language can create ambiguity in the LLM's interpretation. Therefore, to ensure that the LLM understands the structure of the information, we organize the information extracted from past dialogue histories into a JSON format and include it in the prompt as the event details. The details in JSON format are extracted by ChatGPT based on the past dialogue history.

|

#Event details You are Saito (your dialogue partner is Fujita). The same name in the event details refers to you. Events with the same name as the dialogue partner belong to the dialogue partner. If the 'organizer' field has only one name, it is a single-person event (plan), so do not mistake it for a shared event. { "events": [ { "event_id": 1, "organizer": "Fujita", "date": "next month", "location": "Hokkaido", "companions": ["null"], "activities": ["eat seafood", "eat jingisukan (grilled mutton)", "go hiking", "take photos"], "emotions": ["refreshed", "excited"], "status": ["planned"], "source": "heard from Fujita (himself)" }, |

Figure 7. Excerpt from event details.

- Definition and examples of shared-experience-focused utterances: Table 6 shows the content of the definition and examples of shared-experience-focused utterances, one of the components of the proposed prompt. The definition and examples were created based on Tsutsui's research, Structural Analysis of Casual Conversation [8].

|

#Prerequisite Knowledge (Starting a shared-experience-focused utterance) A "chain organization starting with shared-experience-focused utterances (a collection of multiple utterances) is a chain that begins with an utterance that expresses that the speaker and listener share the same information or opinion (or are supposed to). This chain organization starting with shared-experience-focused utterances also includes chains that begin with a question and chains that begin with a report. A chain starting with a question begins with a recall-request utterance, in which the speaker says that they cannot remember information they are supposed to share with the listener, and asks the listener to remember it. A chain starting with a report begins with a narrative utterance in which they recall and talk about an event they experienced with the listener, and a statement-of-opinion utterance in which they express an opinion expecting the listener to have the same opinion. ...[Omitted] #Chain Organization Starting with shared-experience-focused utterances < shared-experience-focused utterances Chain 1> A: Recall request "..., right? / ...?" B: Answer A: Acknowledgment "That's right / Yes / [Repetition]" ...[Omitted] |

Figure 8. Definition and examples of shared-experience-focused utterances.

6. 2. Evaluation Method

Evaluation methods for dialogue systems are often based on user experiments, in which subjects use the system and provide evaluations [10]. This evaluation method incurs costs for recruiting many subjects and requires time for experiencing and evaluating the system, which limits the number of times it can be conducted [20].

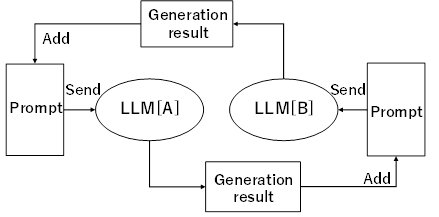

In this study, to conduct experiments with more prompts, we introduced automated dialogue experiments between dialogue systems (Fig. 9). By doing so, we adopted a method that collects and evaluates large-scale dialogue logs without users and streamlines the improvement cycle. The generated dialogues were then subjectively evaluated by the author to assess aspects such as naturalness, consistency, and alignment with shared experiences. In our experiments, each dialogue was limited to 10 turns.

6. 3. Improvement of Contradictions with Self-Attributes

As mentioned in Section 4 1), even when a role name (e.g., "You are Saito") is assigned in the prompt and information such as "Saito went to XX in the past" is included in the dialogue history, the system may generate utterances under the erroneous assumption that “Saito” in the dialogue history refers to a different person. An improvement was observed by placing the prompt instruction statements at the beginning, as in the proposed prompt. When the instruction statements are placed at the end rather than the beginning, however, this issue persists.

Figures 10 and 11 show the generation results when a contradiction with self-attributes was observed and the results from the improved prompt. In this study, all dialogues were generated in Japanese, and the results are presented here in English translation.

|

Conversation |

|

=Turn 1= A (Saito): Next month, You're planning to go hiking in Hokkaido with Fujita, right? That sounds exciting! [Omited] =Turn 6= B (Fujita): I'm really looking forward to it! Plus, we're also planning to go for a run with Fujita and relax at a cafe, so there's plenty to look forward to. Both will be wonderful memories! |

Figure 10. Example Utterance of Contradictions with Self-Attributes.

|

Conversation |

|

=Turn 1= A (Saito): Fujita, we're planning to go for a run together next weekend, right? I'm looking forward to it, but have you thought about where we should stop at a cafe? =Turn 2= B (Fujita): Yeah, I'm looking forward to the run next weekend. I haven't decided on a specific cafe yet, but there are a few nice ones around there. What kind of cafe do you think would be good, Saito? |

Figure 11. Generation Result with the Improved Prompt.

Looking at the generation result in Figure 10, Saito (A) starts the conversation in Turn 1 by saying, "You're planning to go hiking in Hokkaido with Fujita, right?" but in Turn 6, Fujita (B) says, "with Fujita," confirming that it does not recognize its own role.

Looking at the generation result in Figure 11, in Turn 1, Saito (A) says, "Fujita, we're planning to go for a run together next weekend, right?" to which Fujita (B) responds, "Yeah, I'm looking forward to the run next weekend." No utterances that could be seen as contradictions with self-attributes were observed.

6. 4. Improvement of Misinterpretation of Given Information

As mentioned in Section 4 2), even when the system is designed to proceed with the dialogue based on information explicitly included in the prompt (dialogue history from a previous conversation), the LLM may misinterpret that information. In the initial prompt of this study, we included the dialogue history as-is as the common information necessary for shared-experience-focused utterances. With this prompt, utterances that were clearly misinterpretations were observed. To improve this misinterpretation, the proposed prompt includes information such as past events and hobbies, extracted from the dialogue history and organized in a JSON format, as event details.

Figures 12 and 13 show the generation results when misinterpretation of given information was observed and the results from the improved prompt.

|

Conversation |

|

=Turn 1= A (Saito): By the way, that run last weekend was fun, wasn't it! The cafe afterward was relaxing too, let's go again. How was it, you enjoyed it too, right, Saito? (This utterance misinterprets the run scheduled for next weekend as already completed.) =Turn 2= B (Fujita): Yeah, it was fun! The run felt great, and it was nice to relax at the cafe. I'd love to go again. |

Figure 12. Example Utterance of Misinterpretation of Given Information.

|

Conversation |

|

=Turn 1= A (Saito): Fujita, you're planning to eat seafood and go hiking in Hokkaido next month, right? It sounds like a great way to refresh, I'm excited for you. =Turn 2= B (Fujita): Yeah, that's right! I'm planning to eat seafood and Jingisukan and go hiking in Hokkaido next month. It really sounds refreshing, I'm so looking forward to it! |

Figure 13. Generation Result with the Improved Prompt.

Looking at the generation result in Figure 12, A says in Turn 1, "By the way, that run last weekend was fun, wasn't it!" However, the content included in the prompt as the dialogue history states that they had planned to go for a run together the coming weekend. Therefore, the conversation proceeds on the premise that the run has already taken place, which shows a misinterpretation of the given information.

Looking at the generation result in Figure 13, it is confirmed that the system recognizes the Hokkaido trip as a plan, not as an event that has already occurred, and proceeds with the dialogue.

6. 5. Prompt for Shared-experience-focused Utterances

As mentioned in Section 4 3), LLMs tend to have a bias towards "question" and "report" utterance types. Therefore, this study attempts to implement the shared-experience-focused utterances.

Figures 14 and 15 show the generation results from a prompt that does not include content related to as mentioned in Section 4 3), LLMs tend to have a bias towards "question" and "report" utterance types. Therefore, this study attempts to implement the shared-experience-focused utterances. And the results from the proposed prompt.

|

Conversation |

|

=Turn 1= A (Saito): Fujita, you're looking forward to the Hokkaido trip next month, with the seafood and Jingisukan, right? Which one are you most looking forward to? =Turn 2= B (Fujita): That's a tough one, both sound great, but I'm probably most excited about the seafood! I can't wait to taste the fresh seafood. You're looking forward to diving in Okinawa, right, Saito? |

Figure 14. Example Utterance without shared-experience-focused content.

|

Conversation |

|

=Turn 1= A (Saito): Fujita, you said you were looking forward to eating seafood at the Hokkaido event next month, didn't you? =Turn 2= B (Fujita): Yeah, that's right. I'm really looking forward to the seafood. I hope it'll be a nice way to recharge. |

Figure 15. Generation Result with a shared-experience-focused Prompt.

Looking at Figure 14, in Turn 1, Saito makes an utterance that corresponds to the "question" type, "Which one are you most looking forward to?" This shows that shared-experience-focused utterances cannot be generated under normal circumstances.

Looking at Figure 15, in Turn 1, Saito says, "Fujita, you said you were looking forward to eating seafood at the Hokkaido event next month, didn't you?" The utterance "didn't you?" corresponds to a shared-experience-focused utterance.

7. Conclusion

This study aimed to build an LLM-based casual dialogue system to support communication with elderly individuals and reduce feelings of loneliness. As an initial step, we designed and refined a prompt. Specifically, we proposed a prompt that leverages past dialogues and insights from language education. The proposed prompt consists of three components: instruction statements with notes on the role and dialogue, event details with information on events and hobbies extracted from past dialogues, and definitions and examples of shared-experience-focused utterances. Shared-experience-focused utterances are defined as utterances that express that the speaker and listener share the same information or opinions.

To evaluate the system with many prompts, we conducted automated dialogue experiments between dialogue systems. The generated dialogues were then subjectively evaluated by the author to assess aspects such as naturalness, consistency, and alignment with shared experiences. Through this evaluation, we demonstrated that the proposed prompt enables an LLM to more appropriately recognize its role and dialogue content, and to generate natural dialogues that include shared-experience-focused utterances.

However, it should be noted that the evaluations were based on LLM-to-LLM dialogues that were automatically generated and subjectively evaluated by the author. To more robustly assess the system's effectiveness in promoting empathy and social connectedness, future work should include experiments involving real human users interacting with the system.

These findings demonstrate that incorporating shared experiences and language-education-based utterance classification into prompt design improves the coherence and empathetic quality of system responses. This suggests that such an approach can facilitate the development of casual dialogue systems that support social connectedness among the elderly.

References

[1] Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. "Chapter 1, Section 1, Subsection 3: Families and Households." Annual Report on the Aging Society: 2024 (White Paper). Accessed: Sept. 27, 2025. View Article

[2] Ryuichiro Higashinaka. Taiwa Shisutemu no Tsukurikata (How to Build Dialogue Systems). Tokyo: Kindai Kagaku Sha, 2023. (in Japanese).

[3] OpenAI. "GPT-4o mini." Accessed: July 18, 2024. View Article

[4] Che Jiang, Biqing Qi, Xiangyu Hong, Dayuan Fu, Yang Cheng, Fandong Meng, Mo Yu, Bowen Zhou, and Jie Zhou, "On Large Language Models' Hallucination with Regard to Known Facts," in Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), Mexico City, Mexico, 2024, pp. 1041-1053. View Article

[5] Lei Huang, Weijiang Yu, Weitao Ma, Weihong Zhong, Zhangyin Feng, Haotian Wang, Qianglong Chen, Weihua Peng, Xiaocheng Feng, Bing Qin, and Ting Liu, "A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions," ACM Transactions on Information Systems, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 1-55, Jan. 2025. View Article

[6] Ziwei Ji, Nayeon Lee, Rita Frieske, Tiezheng Yu, Dan Su, Yan Xu, Etsuko Ishii, Yejin Bang, Delong Chen, Wenliang Dai, Ho Shu Chan, Andrea Madotto, and Pascale Fung, "Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation," ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 55, no. 12, pp. 1-38, Mar. 2023. View Article

[7] Alberto Blanco-Justicia, Najeeb Jebreel, Benet Manzanares-Salor, David Sánchez, Josep Domingo-Ferrer, Guillem Collell, and Kuan Eeik Tan, "Digital forgetting in large language models: a survey of unlearning methods," Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 58, no. 90, Jan. 2025. View Article

[8] Sayo Tsutusi, Zatsudan no Kozo Bunseki (Analysis of the Structure of Casual Conversations). Tokyo: Kurosio Publishers, 2012. (in Japanese).

[9] Hannah Rashkin, Eric Michael Smith, Margaret Li, and Y-Lan Boureau, "Towards Empathetic Open-domain Conversation Models: A New Benchmark and Dataset," in Proceedings of the Fifty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 2019, pp. 5370-5381. View Article

[10] Yuka Kasai, Rika Shiraishi, and Mitsuhiro Hayase, "Taiwa-gata AI no Kyokan-sei Kojo e no Apurochi" (Approaching Empathy Enhancement in Conversational AI), in Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, Shizuoka, 2024. (in Japanese). View Article

[11] Ryosuke Oshima, Koshi Makihara, Fumiya Matsuzawa, Setaro Shinagawa, Yanjun Sun, Shigeo Morishima, and Hirokatsu Kataoka, "Maruchi-ejento Zatsudan Taiwa ni okeru Taiwa Hatan Bunseki" (Dialogue Breakdown Analysis in a Multi-Agent Non-Task-Oriented Conversation), in Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, Shizuoka, 2024. (in Japanese). View Article

[12] Nelson F. Liu, Kevin Lin, John Hewitt, Ashwin Paranjape, Michele Bevilacqua, Fabio Petroni, and Percy Liang, "Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts," Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, vol. 12, pp. 157-173, 2024. View Article

[13] Qing Lyu, Shreya Havaldar, Adam Stein, Li Zhang, Delip Rao, Eric Wong, Marianna Apidianaki, and Chris Callison-Burch, "Faithful Chain-of-Thought Reasoning," in Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing and the 3rd Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Nusa Dua, Bali, 2023, pp. 305-329. View Article

[14] Sewon Min, Xinxi Lyu, Ari Holtzman, Mikel Artetxe, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Hannaneh Hajishirzi, "Rethinking the Role of Demonstrations: What Makes In-Context Learning Work?," in Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022, pp. 11048-11064. View Article

[15] Tom Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared D. Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Sandhini Agarwal, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Gretchen Krueger, Tom Henighan, Rewon Child, Aditya Ramesh, Daniel Ziegler, Jeffrey Wu, Clemens Winter, Christopher Hesse, Mark Chen, Eric Sigler, Mateusz Litwin, Scott Gray, Benjamin Chess, Jack Clark, Christopher Berner, Sam McCandlish, Alec Radford, Ilya Sutskever, and Dario Amodei, "Language Models are Few-shot Learners," in NIPS '20: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Dec. 2020, pp. 1877-1901. View Article

[16] Andrea Madotto, Zhaojiang Lin, Genta Indra Winata, and Pascale Fung, "Personalizing Dialogue Agents via Meta-Learning," in Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Jul. 2019, pp. 5454-5459. View Article

[17] Patrick Lewis, Ethan Perez, Aleksandra Piktus, Fabio Petroni, Vladimir Karpukhin, Naman Goyal, Heinrich Küttler, Mike Lewis, Wen-tau Yih, Tim Rocktäschel, Sebastian Riedel, and Douwe Kiela, "Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks," in NIPS '20: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Dec. 2020, pp. 9459-9474. View Article

[18] Murray Shanahan, Kyle McDonell, and Laria Reynolds, "Role-Play with Large Language Models," in Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023. View Article

[19] Jie Ma, Ning Qu, Zhitao Gao, Rui Xing, Jun Liu, Hongbin Pei, Jiang Xie, Linyun Song, Pinghui Wang, Jing Tao, and Zhou Su, "Deliberation on Priors: Trustworthy Reasoning of Large Language Models on Knowledge Graphs," arXiv:2505.15210, 2025. View Article

[20] Abigail See, Stephen Roller, Douwe Kiela, and Jason Weston, "What Makes a Good Conversation? How Controllable Attributes Affect Human Judgments," in Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minnesota, Jun. 2019, pp. 1702-1723. View Article